The Questions That Never Leave Us

A Lifetime Journey from Teenage Doubt to Elder Wisdom

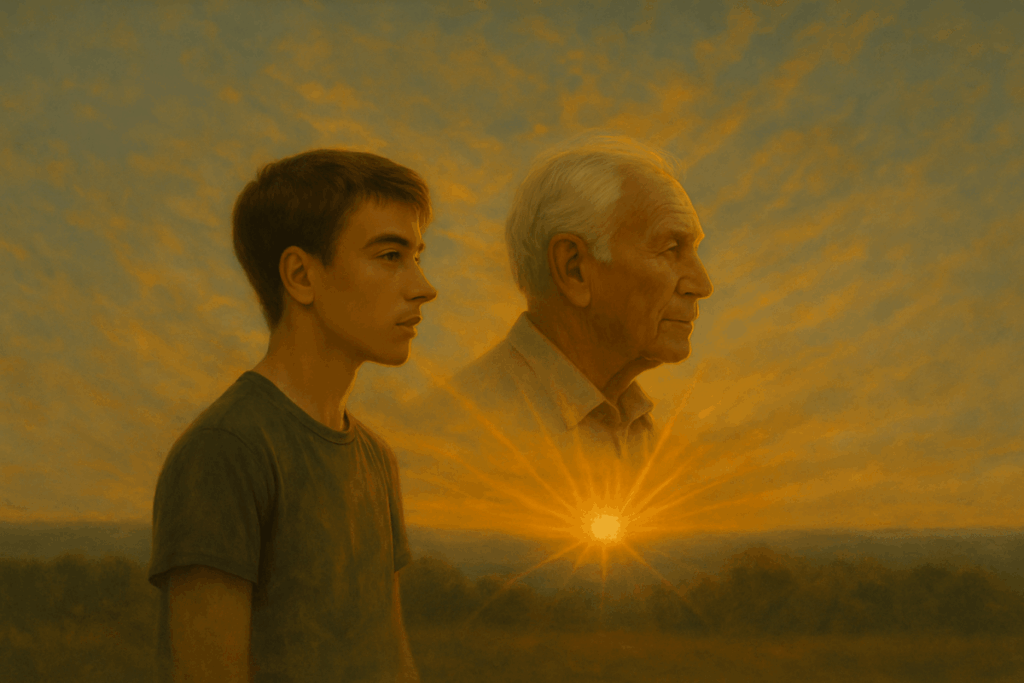

Throughout our lives, the core questions of identity, purpose, and meaning that first emerge in our youth continue to shape us, evolving in complexity but remaining fundamentally central to the human experience.

What constitutes a worthwhile life? Adolescents ponder their identities, middle-aged adults question past decisions, and elders shift to legacy and acceptance. The philosophical concerns we first encounter in youth persist as lifelong companions, growing in complexity as we age.

The Awakening: Philosophical Questions About Adolescence

Adolescence is when abstract questioning becomes conscious. Teenagers don’t just wonder, “Who am I?”—they experience it daily in evolving identities, social ties, and aspirations. Plato remarked that young minds entertain “a game of argument and criticism” without seriously considering what replaces abandoned customs. This restlessness, sometimes seen as rebellion, marks the first stirrings of independent consciousness.

The teenage philosophical repertoire is remarkably large, but intensely personal:

- Identity and Selfhood: “If you had another name, would you be a different person?” or else “Are people born with a specific personality, or is it the result of their circumstances?”

- Morality and Justice: “What is the difference between good and bad people?” Furthermore, “Is justice always equitable?”

- Existence and Meaning: “What is the meaning of life?” and “If there is a perfect balance between work and life?”

- Love and Relationships: “What Is Love?” Furthermore, “Do soulmates exist?”

Aristotle said youth are “driven by emotion and appetite” and lack prudence from experience. This emotional intensity fuels their philosophical questions, making issues of fairness, belonging, and purpose feel personal rather than abstract.

Eastern traditions approach this stage with a unique understanding. The Bhagavad Gita, a battlefield discourse, recognises youth’s inner turmoil with compassion. “The mind is restless, turbulent, strong, and obstinate,” observed Arjuna—a feeling familiar to every burdened student. The text offers a path: “By practice and detachment, it can be controlled.” It teaches that “you are what you believe in. You become what you believe you can be,” underscoring self-perception’s impact on identity creation.

The Shifting Landscape: Philosophical Questions for Adults

As youth enter adulthood, their philosophical issues evolve, becoming intertwined with the practical realities of life. According to sociological studies, this transition is becoming more prolonged and individualised, with young people alternating between education and employment while navigating complex relationship patterns.

“Feeling like an adult” doesn’t always match life milestones. Research finds that the link between life structures and role timing is complex. We don’t become adults by checking boxes—we do so by comparing ourselves to social standards.

This negotiation reshapes previous philosophical questions:

- From “Who Am I?” to “Who Have I Become?”: The identity dilemma shifts from possibility to lived reality, encompassing career, relationships, and sometimes parenting.

- From “What is love?” to “How do I sustain love?”: Romantic idealism becomes personal assessments of contribution and purpose, relationships, financial stresses, and shifting circumstances.

- From “What is the meaning of life?” to “Does my particular life have meaning?”Abstract wonderings become personal assessments of contribution and purpose.

- From “What is justice?” until “What are my responsibilities?”: Societal critiques lead to considerations about individual accountability within systems.

As we mature, the concept of agency—our ability to make decisions and shape our lives—becomes increasingly important. Our philosophical concerns are increasingly reflecting the conflict between our goals and our limitations. Our question isn’t simply “What is possible?” but also “What is possible for me, given my responsibilities, history, and circumstances?”

The Deepening Inquiry: Philosophical Questions in Late Life

If adulthood mixes philosophy with daily life, old age often revives philosophical concerns, this time shaped by experience and mortality. Studies show ageing brings a shift in existential questioning.

A phenomenological study of adults aged 55-92 who claimed “seeing no future for oneself” revealed four connected experiences:

- Not sharing ordinary life (feeling severe loneliness despite occasional social contact)

- Looking for new commitments (seeking but unable to find significant engagement)

- Facing current losses and future fears (dealing with reduced capacities while fearing greater deterioration)

- Imagining not waking up in the morning (thinking about death as a personal experience rather than an abstract abstraction)

The essence of these experiences is described as “losing zest for life.” This isn’t always depression, but a change in perceiving time, options, and meaning. Future possibilities narrow, and the philosophical focus shifts from what will be done to evaluating what has already occurred.

Eastern philosophy and old Indian writings provide invaluable tools for this life stage. When one’s traditional “duties” are reduced, the Bhagavad Gita’s concept of executing duties without attachment to fruits becomes more relevant. The text warns: “You have a right to perform your prescribed duties, but you are not entitled to the fruits of your actions”. This wisdom promotes a move away from achievement-based affirmation and towards the worth inherent in being and aware presence.

Lao Tzu, of the Daoist tradition, offers wisdom on ageing: “Do you have the patience to wait till your mud settles and the water is clear?” As output fades in later life, clarity comes from rest, not striving.

The Unbroken Thread: How Our Questions Developed

Tracing these questions over the life cycle reveals remarkable patterns of continuity and change. The teenage inquiry “Who am I?” develops into the adult question “What have I made of myself?”, which in turn becomes the elder’s question “Who was I, in the end?”. Each variation expresses the same fundamental concern with identity and meaning, but via various temporal lenses: future potential, present duty, and past integrity.

Teenage questions like “Is there a God?” and “What is reality?” mature as we age. Adults consider how beliefs affect ethics and resilience, while elders wonder if convictions provide comfort at life’s end. The Bhagavad Gita teaches that spiritual questions adapt to each life stage, not disappear.

Plato noted that in societies that value luxury and rapid fulfilment, young people become “soft when pampered and affluent”. Today’s “culture of completion,” which frequently marginalises older people, shapes how they view their existential concerns. A culture that prioritises productivity struggles to recognise the distinct but equally important contributions of contemplative elder wisdom.

Embracing the Questions for Life

The most fundamental philosophical issues we ask as teenagers never fully leave us. They serve as the thread that runs through a conscious human life, evolving with us. The teenage search for identification evolves into the adult construction of a life, which is then integrated by the older into a meaningful whole. The young questioning of authority evolves into the mature navigation of duty, which becomes the elder’s pondering on what endures.

Perhaps the ultimate wisdom, as indicated by both Western and Eastern traditions, is to reconcile with the issues themselves. According to Paul Tillich, “only the philosophical question is perennial, not the answers”. The Bhagavad Gita teaches resilience via non-attachment to specific outcomes: “Work done with anxiety about results is nowhere near work done without such anxiety, in the calm of self-surrender”.

Jack Kornfield wonderfully summarises the essence of a well-examined life: “How well did you love?” “How fully did you live?” “How deeply did you let go?” These questions begin in childhood, gain substance in age, and reach their peak resonance in our latter years. They are ultimately the questions that define our humanity.

How a Therapist Can Guide You Through Life’s Biggest Questions and Find Peace

When you’re dealing with seemingly unanswerable questions, it can feel like you’re adrift in a fog with no compass. The profound issues about identity, meaning, and purpose that troubled you as a teenager may have accompanied you into adulthood, albeit with greater complexity, repercussions, and potentially urgency. You could be thinking, “I should have figured this out by now,” but the truth is that these questions are not designed to be answered once and for all. They’re intended to be lived. And this is where a great therapist may be your most important companion—not by providing solutions, but by helping you develop the inner resources to live the questions themselves.

Establishing a Sanctuary for Your Deepest Wonderings

Imagine entering into a setting where your most pressing questions are not rejected as overthinking, but rather treated with the respect they deserve. In this context, your therapist provides a sanctuary—a confidential, nonjudgmental space where you can express what may be too difficult or abstract to convey elsewhere. For example, when you tentatively say, “Sometimes I wonder what the point of it all is,” they do not rush to console you with platitudes. Instead, they should gently say, “Tell me more about that wondering. Where does it live in your body when it comes up?” This marks the beginning of a deeper exploration.

Existential worries are not stigmatised here. A skilled therapist recognises this and helps normalise these thoughts, seeing them not as signs of disorder, but as reflections of your capacity for depth. Instead of battling these questions, you learn to engage with them productively.

Helping You Decode Your Inner World

Your therapist serves as an expert interpreter between your confusing thoughts and your deeper wisdom. They help you identify patterns you would otherwise overlook. When you frequently ask, “Who am I really?” they may help you understand how this issue arises, particularly when you make decisions to suit others rather than yourself. They facilitate the transition from the philosophical to the human realm.

Linking Eastern Wisdom with Western Psychology

A culturally sensitive therapist can help you explore the wisdom traditions that are meaningful to you. They could implement mindfulness practices based on Buddhist psychology that reflect the Bhagavad Gita’s teaching: “For those who have conquered the mind, it is their best friend. For those who have not done so, the mind is the most powerful enemy.” Meditation and present-moment mindfulness help you see your existential fears without becoming obsessed by them.

Similarly, when you struggle with concerns regarding pain and acceptance, they may refer to the Stoic philosophy of Epictetus, who reminded us: “We cannot choose our external circumstances, but we can always choose how we respond to them.” Your therapist can assist you in transitioning from abstract theory to daily practice, such as through journaling activities that distinguish between what is within and what is outside your control.

Transforming Questions from Obstacles To Guides

A profound shift happens when you stop seeing philosophical questions as problems to solve and start letting them guide you toward a more honest life. Your therapist supports this transformation.

When you enquire, “Who am I?”, you are not given an identity to embrace. Instead, they might walk you through value clarification exercises, helping you discover what is so important to you that you would pursue it even without external confirmation. They assist you in recognising when you’re living according to others’ expectations rather than your own inner compass. Your therapist sets the conditions for self-acceptance to thrive.

When you question the meaning of life, they don’t provide a general answer, but help you in identifying your purpose through exploratory conversations, whether in relationships, creativity, service, learning, or experiencing beauty.

When you examine mortality and impermanence, they help you transform your fear of endings into inspiration to live more fully in your current relationships and activities.

Carrying What You’ve Gained

You’ll find, as both ancient wisdom and modern psychology suggest, that peace of mind arises not from having all the answers, but from trusting your ability to navigate life’s questions. As you internalise this, you create a secure inner base—a steady sense of safety that helps you meet uncertainty with resilience. The trip through treatment is similar to the hero’s journey—you explore into unknown parts of yourself and return with hard-won insight to give through your actions.

Embrace your journey and seek guidance to face life’s questions with courage. Take the next step by reaching out to a therapist and discover the transformative power of exploring your biggest questions. The opportunity to find peace and live authentically is within your reach—begin today.

Click www.hopetrustindia.com for an online appointment with a therapist.