In Search of My First ‘Pot’ of Gold

– Chander Mahadev

How an addict got caught up in the heady early ‘70s and progressed into addiction

I have firmly believed that most great souls and saints reach the zenith of existence by scaling mountains and shedding light on us mortals. We call them saints or seers, but what would we call those seekers who prefer to go, but there were also seekers like me who preferred to go down to the depths of the underworld to search for the unknown, and those of us who were lucky would emerge with the distilled nectar of existence. Was it because my name had a hint of Lord Shiva in it, who drank up the proverbial poison to purify the Amrit, nectar of immortality, following the churning of the ocean?

How this search for the nether world started, I can’t say. However, as a young boy, there was a disturbing thought that used to make me shudder to the bones. I used to see that wherever I went in the city of Delhi, a wastewater stream (nullah in local parlance) was sure to follow me. I wondered why the stench of the wastewater always greeted me wherever I went. Was it God’s curse, or was it to remind me that this was the proverbial Mary’s lamb that was sure to follow me till my death? Or was it to remind me to shed my stinking thinking and become more caring and purer? Was it to tell me that life becomes what I make it out to be? Was there an underlying fear that all the nocturnal habits I was beginning to indulge in (like smoking cigarettes and pot) at the age of 16 were haunting my conscience, I can never say.

How this search for the nether world started, I can’t say. However, as a young boy, there was a disturbing thought that used to make me shudder to the bones. I used to see that wherever I went in the city of Delhi, a wastewater stream (nullah in local parlance) was sure to follow me. I wondered why the stench of the wastewater always greeted me wherever I went. Was it God’s curse, or was it to remind me that this was the proverbial Mary’s lamb that was sure to follow me till my death? Or was it to remind me to shed my stinking thinking and become more caring and purer? Was it to tell me that life becomes what I make it out to be? Was there an underlying fear that all the nocturnal habits I was beginning to indulge in (like smoking cigarettes and pot) at the age of 16 were haunting my conscience, I can never say.

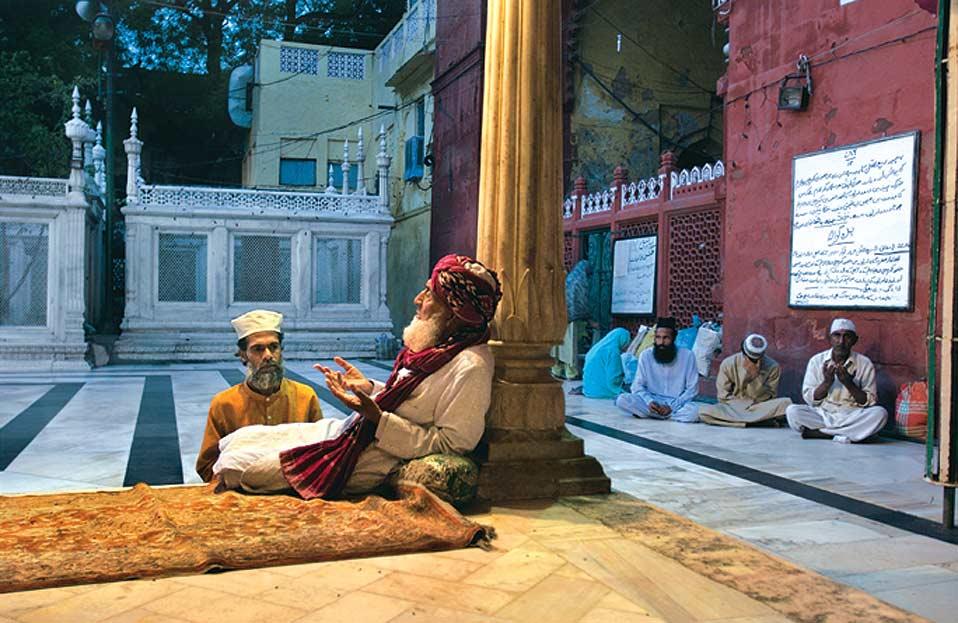

Why I am sharing this ‘dark’ if not dreadful thought with you is that as schoolmates, we would often sit in the arc-shaped, neatly laid out park that skirted the nullah in front of our homes in Nizamuddin West. As young deviant friends, we would hold marathon sessions on how to deal with such worldly and vexing issues. Some of my friends suggested we drink liquor and snuff out the stink, while others like me thought that if we smoked a flavorful Hashish ‘pot’ (chillum), we would be able to find a better and more concentrated solution. Well, there was no harm in trying! However, the park that skirted around Nizamuddin West slowly became the leitmotif of our existence. Since our parents did not approve of our guitar-strumming and flute-playing ways, the park was our collective address. We would sneakily assemble at 9 pm once we had had our dinner and hold forth till midnight.

I soon began to be called the ‘Garhwali Mundu’ by irritated senior residents (since Garhwal, now in Uttarakhand, is where most house helps came from, and they loved to play the flute in their free time). I was fascinated with this wind instrument, especially since a Sufi Dervish had told me it was the way to connect with my inner self and become one with God.

Even as we pored over Aldous Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’, ‘Time Must Have a Stop’, and Virginia Woolf’s ‘View from a Room’, our nocturnal hash-filled book reading sessions became our unrelenting quest for seeing knowledge and conquering the unknown. We were not openly feted or greeted for our wayward ways, but we hardly cared. For the sake of privacy, I will not name the five or six core group of friends that comprised our lot, but for narration, I will use acronyms to tell this outlandish and otherworldly story that I am about to share with the world at large. I can also give no assurance that some of the incidents I have shared could be from another time and space, since what I am talking about goes back five decades in time. There is also the need to use poetic license to tell a riveting story.

These digressions aside, the underlying thought among most of us was that we should emerge as long-haired, Baba-like intellectuals with a strong smattering of Western thinking, much like the Indian versions of Hippies. They had begun to pour into India. Their defiance, bold approach, and love for the dangerous appealed to us.

I, on my part, believed I had the makings of a great communicator, and to achieve this elusive goal, I wanted to be a great thinker and a better writer. I also recall that in a song by the English band Moody Blues, it was said that ‘thinking is the best way to travel.’ I loved the lyrics of this song. Others like the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, KL Saigal and Ravi Shankar became the soothing balms to our restless souls. They became our chosen Muses. Deeply influenced by this cultural and musical potpourri, we shaped our intoxicated minds to try to become the Huan Tsang and Ibn Battuta of modern India.

1970 was a watershed year in many ways. Our high school exams had just gotten over. My friends and I were mesmerised by the never-ending stream of American and European travellers who had begun to wend their way to India, armed with their trailer vans, their girlfriends, dogs and guitars. Most of them would proudly display horn-shaped Turkish chillums and top-quality Afghani Charas (hashish from Mazare Sharif) and would then drop anchor at the Scout Camp, in Nizamuddin, next to the grand old Humayan’s tomb. They would recount tales of valour and how they overcame daunting odds to reach Delhi. Despite the stench of the nullah, they would sing hosannas of praise for the Hindu way of life, on the lives of the sadhus, the heady ideas of the fakir, and hold forth on the land of Krishna. Make love, not war was the cry in the US, since the country had gotten mired in the Vietnam War. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (and his wonky idea of levitation) unwittingly became India’s first cultural brand ambassador. Fusion music, too, was beginning to raise its head, and Nizamuddin was turning into Niza-town, considering the cultural mix that had started to emerge.

Our colony was slowly, albeit unwittingly, being turned into a neo-Bloomsbury group. Theatre icons like Abraham Alkazi, painters like M F Hussain, Tyeb Mehta and Jatin Das, and movie directors like Sai Paranjpe, and more theatre directors like Marcus Murch and Barry John had begun to dot the Nizamuddin landscape, though mindscape would be a more appropriate term. We soon realised that if we were to make a mark in front of iconic giants like these, we needed to do something outstanding or even outlandish to be counted as high-thinking young men of mettle.

Finally, four of us, including Beanie, Nits and M, decided that we too needed to switch on the adventure button and do the impossible. We decided that, for the sake of bravado or braggadocio, call it what you will, we would trek all the way to Manali from Delhi and back since we all had so much time on hand. We had heard of stories about Manali being a pure and pristine, misty mountain haven untouched by tourists and traders. Now, what route to take and how to go about it was left to our own collective imagination. There was no Google to help us then, so we went to the British Council library to do our research. While the thought sounded preposterous, we decided to confront our parents with this idea. Surprisingly, the other three sets of parents said we should all meet and then take a call. My father, being the strictest of the lot, had other ideas. He didn’t turn down the proposition. Instead, he said if all four of us could walk down to Palam airport and back, he would give us his reply. Hugely excited and pumped up, we decided to accept this challenge. On the scheduled Sunday, my father emptied our pockets to make sure we didn’t have money.

By 5.30 am on a crisp winter morning, we set off to pass our first endurance test. We reached Palam airport in a little over three hours, and without taking a break, we decided to drink a cup of chai from a roadside vendor who was himself taken in by our ‘far-fetched’ story. We headed back to our homes in Nizamuddin in six hours and felt like we had conquered Mt Everest. Some of us felt like Yuri Gagarin, the first Russian cosmonaut to go to space, and within a week, we began preparations.

M, our Sardar hippie friend, handed out a list of tools like a Swiss knife, haversack, bedroll and a pair of sneakers to help us prepare for our tryst with destiny. But even after we had stocked up on tinned food like baked beans and sardines, along with glucose biscuits, my father was not willing to give me the green signal. But as they say, luck favours the brave, and my father, who worked for a UN agency, was asked to head for a South Asian country on an official visit. I then went in for the kill. I was able to convince my mom since she was my co-conspirator in all my adventures. With fear in her heart, she reluctantly agreed to let me go when the four of us collectively assured her that we would make a landline call once every three days. With a princely sum of Rs 70 in each pocket, the four of us set out on an impossible mission to conquer Manali on foot. Untrained and with no navigation tool, except for enquiries from friends and foes, we set forth.

M, our Sardar hippie friend, handed out a list of tools like a Swiss knife, haversack, bedroll and a pair of sneakers to help us prepare for our tryst with destiny. But even after we had stocked up on tinned food like baked beans and sardines, along with glucose biscuits, my father was not willing to give me the green signal. But as they say, luck favours the brave, and my father, who worked for a UN agency, was asked to head for a South Asian country on an official visit. I then went in for the kill. I was able to convince my mom since she was my co-conspirator in all my adventures. With fear in her heart, she reluctantly agreed to let me go when the four of us collectively assured her that we would make a landline call once every three days. With a princely sum of Rs 70 in each pocket, the four of us set out on an impossible mission to conquer Manali on foot. Untrained and with no navigation tool, except for enquiries from friends and foes, we set forth.

To be continued…